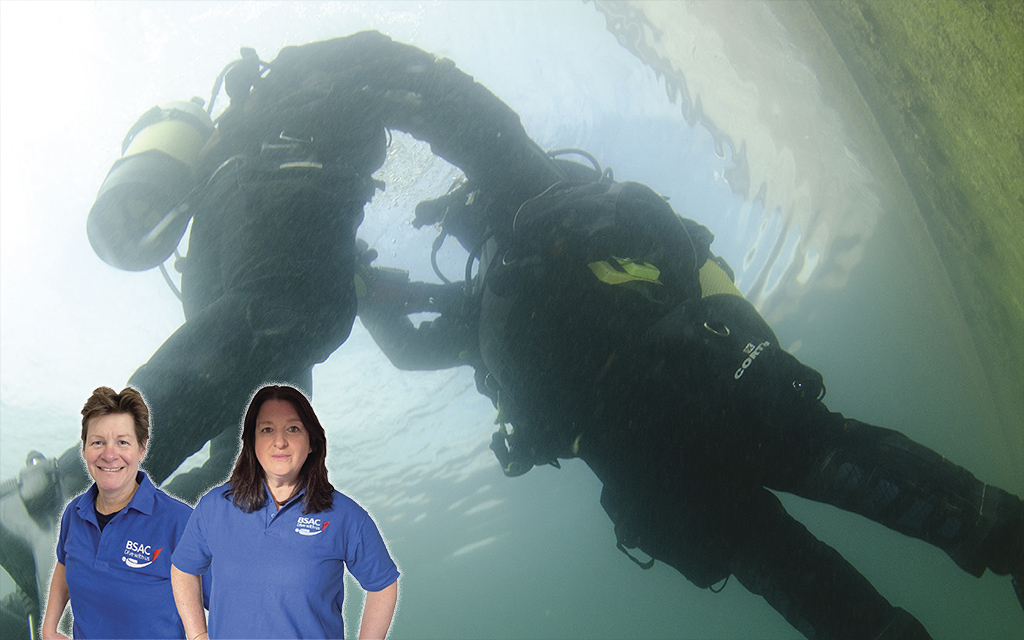

In this month's SCUBA Magazine BSAC National Diving Officer Sophie Rennie, and Head of Diving and Training Sophie Heptonstall, discuss the Controlled Buoyant Lift (CBL).

THE QUESTION:

The controlled buoyant lift (CBL) is a key lifesaving skill, but it’s hard to simulate unpredictability in training. What’s it like performing a rescue in a real-world scenario?

Sophie Rennie answers

The basic principles of the skill remain the same in a real-world scenario, and it’s these core skills a diver will draw upon if needed. The key steps are positive contact, a controlled casualty lift and making the casualty buoyant on the surface, followed by the rescuer ensuring they themselves are buoyant.

The variables in real life are often things like kit configuration. For example, the full variation of single, twin-sets, pony cylinders, sidemount and CCR (closed-circuit rebreather) are not often covered in practice drills for CBL. But they are among the variety of kit configurations many of our divers use in open water, and we often change buddies on different trips. The main difference with kit variations is simply balance; if unconscious, the casualty may balance differently, but the rescuer should be able to feel this and adjust as necessary to manage the lift. The rescuer doesn’t need to worry too much – as long as they have positive contact and positive lift towards the surface.

No one can predict how they will react in a real-life scenario, but the aim of rescue training throughout all levels of the BSAC Diver Training Programme is to commit these essential skills to muscle memory to ensure they are available if ever needed. Don’t underestimate the instinct to help in the event of an emergency.

In practice, once the skill is done you can move on. But in real life, divers need to be much more aware of aftercare for both the casualty and the rescuer. The rescuer has been placed in a stressful situation and that affects people differently. Often talking to those involved or in the club can be beneficial, but there are also post incident support services BSAC members can access and are offered when an incident report is submitted.

Sophie Heptonstall expands

If you’ve been unlucky enough to have to perform a Controlled Buoyant Lift (CBL) on anyone, then it is mostly exactly the same as when you have performed it in a training scenario, but maybe with a little more stress and definitely an elevated heart rate. After all, a few endorphins will kick in, as they do in any emergency situation.

If you’ve been unlucky enough to have to perform a Controlled Buoyant Lift (CBL) on anyone, then it is mostly exactly the same as when you have performed it in a training scenario, but maybe with a little more stress and definitely an elevated heart rate. After all, a few endorphins will kick in, as they do in any emergency situation.

I once had to bring a hyperventilating diver to the surface from 20m, and I had to lift them as well as holding their regulator in their mouth. Had they spat it out, they would have inhaled water and drowned because they could not control their breathing. Fortunately, they seemed to know I was trying to rescue them.

On another occasion I had to lift a diver who was having a panic attack. My rescues have been on conscious casualties. It’s important to look them in the eye and try to get them to understand that you are well equipped to rescue them. Reassurance in your eyes and holding them tight helps. They will want to shrug you off once they get to the surface, as they will want all the air space they can get, but it’s important to make sure you are both fully buoyant and that their head is safely clear of the water at the earliest opportunity.

Post-event and when all is calm again, it’s good to talk through how you carried out the rescue, what went right and points for improvement. We know the CBL is a good skill to practise, and this is why we include it in entry level training.

Article 'Real world rescues' by Simon Rogerson first published in SCUBA magazine, Issue 154 April 2025.

Author: Simon Rogerson | Posted 26 Apr 2025

Author: Simon Rogerson | Posted 26 Apr 2025