So you think barnacles are dull? Think again, says science correspondent Karen Boswarva...

Barnacles are an often-overlooked group of animals, unless you’re gloveless or walking barefoot on a rocky shore – ouch! They are neither flamboyant or brightly coloured, and rarely scream LOOK AT ME, but have you ever stopped to gaze at their gentle, rhythmic feeding arms? I urge you to do so. They have quite the hypnotising and calming effect, opening their diamond shaped trap door to rasp for tiny food particles as they float by.

Globally, there are more than 1,400 species of this unassuming member of the crab family. You wouldn’t think it, but they are in fact crustaceans and display the same characteristics as crabs, lobsters and prawns. They start life as a small larva drifting in the currents. The big difference is that most will eventually settle on a stationary surface such as a rock or a wreck and secrete a hard protective shell made of calcium.

Those preferring the nomad lifestyle grow long neck-like appendages and wander the world’s oceans attached to flotsam and jetsam. Others will grow massive, hitching a ride on the backs of sea turtles and whales, sometimes to the detriment of the animal. Sea turtles can be plagued by the weight of barnacles growing on their shells. The size, shape, and quantity of barnacles causes extra drag that affects their ability to swim properly. Imagine trying to swim with a big bag of rocks stuck to your back! Sometimes, when the animals are in great distress, humans will intervene to temporarily remove this weighted burden.

Globally, there are more than 1,400 species of this unassuming member of the crab family

Then there are barnacles that have a darker, more sinister side. The crab hacker barnacle Sacculina carcini is a species of parasitic barnacle found throughout the UK. It infects swimming crabs, most commonly the shore crab Carcinus maenas, changing both their behaviour and physiology, rendering the crabs sterile in the process.

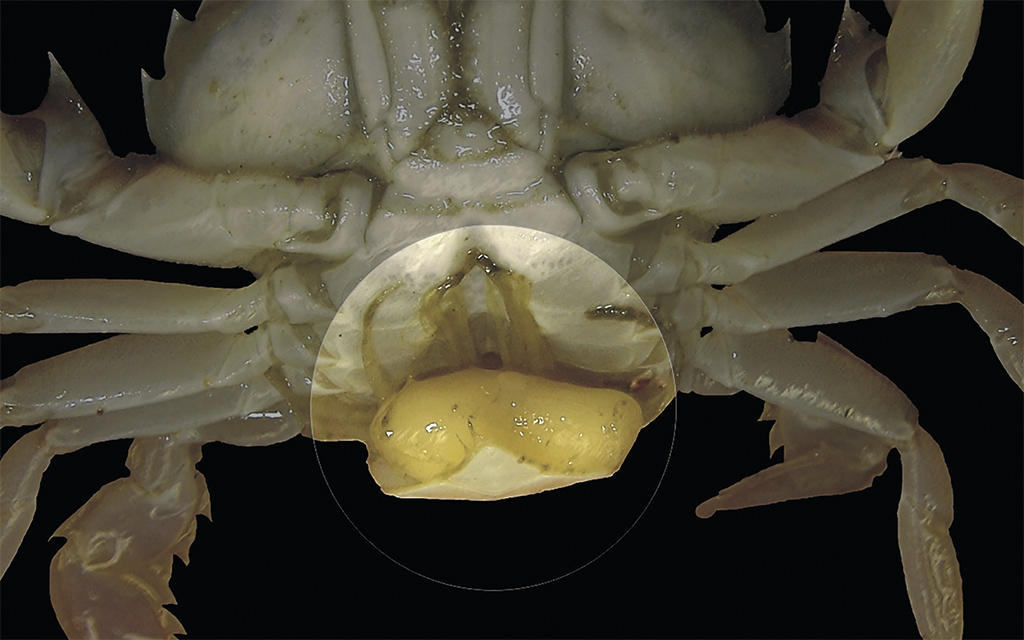

This zombie attack occurs in two stages. Stage 1: the female larvae called kentrogen infects the crabs’ tissues. Finger-like rootlets form in the crab’s body, including the reproductive system. The rootlets absorb nutrients and start to grow. Stage two: up to 36 months later a large creamy-yellow sac will emerge from the underside of the crab. The sac contains developing eggs, which can then be fertilised by male crab hacker larvae called cyprids that are floating around in the water. The cyprids fertilise the eggs and the larvae – called nauplii – develop in the sac until they are ready to be released and start their own search for a host.

Unfortunately, this partnership offers no benefit to the crab. Infected male shore crabs can no longer produce sperm. The abdomen widens, making them look and act like females. Infected female shore crabs will stop producing eggs but behave like they are carrying eggs. The infected crabs are unable to moult, become more prone to infection and are therefore unlikely to survive once the parasitic larvae are released. Crabs that do survive then play host to another cycle of infestation. The old sac will deteriorate and form a scar on the abdomen before a new sac emerges 36 months later.

Infections are thought to be quite common. Fishermen will sometimes find these parasitic barnacles when they check their catch. You may find them too when rock pooling or crabbing.

When you’re diving, look out for crab behaviour. Crabs that are ‘in berry’ (with eggs) will often raise their legs up, lifting their abdomen off the seabed. This allows fresh sea water to flow over their brood and for you to do a quick scan for these creepy stowaways. Bet you’ll never look at crabs (or barnacles) the same way again.

Article ‘Zombie barnacles!’ by Karen Boswarva first published in SCUBA magazine, Issue 151 December 2024.

Author: Karen Boswarva | Posted 16 Dec 2024

Author: Karen Boswarva | Posted 16 Dec 2024