Becky Hitchin turns her gaze to the unsung heroes of the marine world, inviting us all to a plankton party.

This month, we’re going to look at something you’ll (almost) never see when diving, but is guaranteed to surround you every time you get in the water. We’re talking about plankton, in all its myriad forms. The plankton surrounding us when we dive is a wonderland of species that drift around in water currents, either floating passively in the water or actively swimming. Plankton are at the base of all the marine food chains around the UK, meaning they are critical in maintaining and supporting all the marine and freshwater food webs with all the species we love watching and photographing. Without plankton, entire food webs around the world would likely collapse.

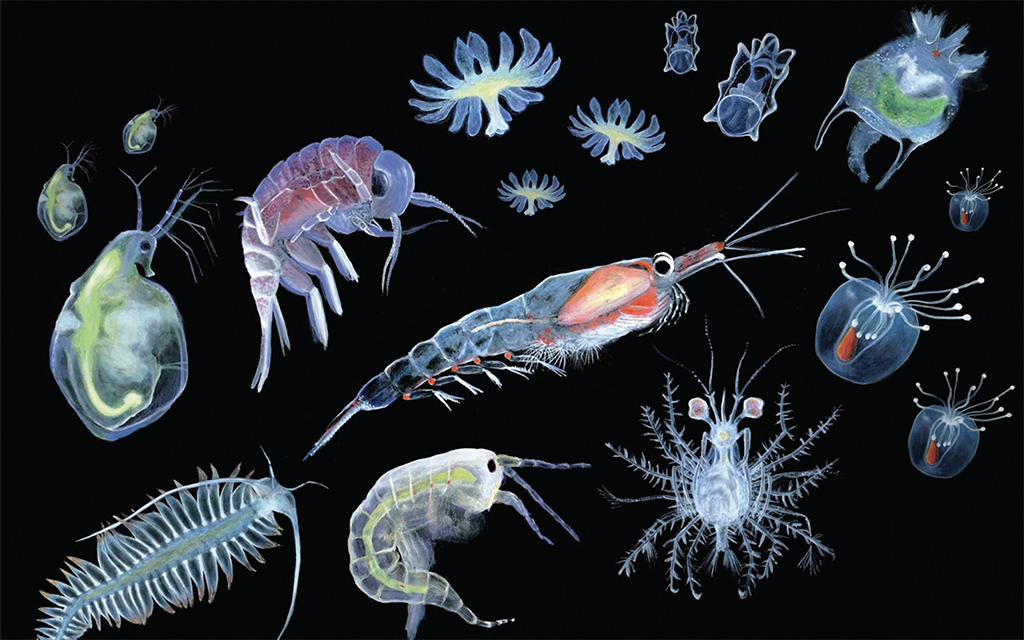

Phytoplankton are plants, containing chlorophyll and needing sunlight and nutrients to grow. They photosynthesise and convert carbon dioxide to oxygen and amazingly are responsible for up to half of the oxygen we breathe. Zooplankton, on the other hand, are small – or very small – animals. Some of these animals spend their entire lives in the plankton, while others are only in the plankton as larvae. Zooplankton includes animals such as copepods, and the larval stages of so many things – including worms, molluscs, barnacles, crabs and lobsters and echinoderms.

millions and millions of tiny plants and animals invisibly swimming and floating around you

The body forms they take in the plankton are marvellous and miraculous, including iridescent lights strobing along tentacles and pseudopodia, radial symmetry, bilateral symmetry, long trailing antennae, shapes you’ve not seen anywhere else in the marine world. The phytoplankton are eaten by small zooplankton, which are in turn eaten by other zooplankton, small fish and crustaceans. These are then eaten by larger predators, and so on up the food web. There are also some large animals that directly eat plankton. Blue whales, for example, can eat up to 4.5 tons of krill every day.

However, as you are probably expecting, plankton has been affected by change in ocean temperature and ocean acidification. Abundance has been decreasing, something we know because we have a long record of plankton abundance thanks, not least, to regional-scale offshore plankton monitoring provided by the Continuous Plankton Recorder (CPR) survey run by the Plymouth Marine Laboratory, which has been using volunteer commercial and research vessels to collect a consistent plankton time-series since 1958.

Recent monitoring analysis shows that plankton has undergone multi-decadal, whole-region-scale change over the North-West European shelf. CPR data revealed a big increase in the amount of larvae in the plankton, with the last decadal mean over twice as high than the beginning of the time-series in 1950s. Abundance of full-time plankton, on the other hand, is decreasing hugely, with the last decadal mean approximately half that of the beginning of the time-series. These changes are consistent throughout the North Sea and most of the Celtic Seas.

These changes can be seen to correlate with sea surface temperature, providing strong evidence that the increase in larvae in the plankton is driven by climatic and oceanographic change. Over smaller spatial scales, the increasing trends in amount and types of larval plankton is shown to be largely driven by an increase in echinoderm and decapod larvae. How interesting is that, when bivalve larvae are showing decreases over the same time periods.

So next time you go diving, remember all those millions and millions of tiny plants and animals invisibly swimming and floating around you. Providing our oxygen and keeping our planet in balance.

Article ‘The drifters’ by Becky Hitchin first published in SCUBA magazine, Issue 146 June 2024.

Author: Becky Hitchin | Posted 07 Aug 2024

Author: Becky Hitchin | Posted 07 Aug 2024