Inspired by Zoological Society London’s native oyster quest photography competition last year, BSAC Expeditions Coordinator Andy Hunt is taking action to help our vulnerable native oysters with a new BSAC diving project. And he needs your help!

According to Zoological Society London (ZSL) wild native oyster beds of Ostrea edulis are probably one of the most endangered marine habitats in Europe. In the UK wild native oyster populations have declined by over 95% over the past 200 years due to a variety of effects including historic overfishing, habitat loss, pollution and introduction of diseases.

These once abundant critters provide habitat for other species, store away carbon and filter up to 200 litres of seawater a day.

Oysters provide enormous benefits in the form of ecosystem services. The shellfish are known as ‘ecosystem engineers’ because they provide the foundation for entire ecosystems – filtering water and providing vital food and habitat for coastal wildlife.

BSAC is now working collaboratively with other agencies to support the recovery of the UK’s native oysters and is now launching an exciting new environmental project.

Led by Expeditions Coordinator Andy Hunt, the new BSAC initiative, ‘Operation Oyster’, will provide an opportunity for divers to contribute something environmentally valuable in the course of their normal diving, using tools and tech readily available to the budding citizen science diver.

The project aims to gather data on the native oyster populations in and around the British Isles to support work already underway with other agencies, with the aim of helping restore oyster populations and the seabed.

Andy needs a core team of about four volunteers with skills in marine science, video editing, social media and applying for grants to help run a large BSAC citizen science project. He also, in time, will need members, clubs and centres to participate to help deliver the project.

Contact Andy at expeditions@bsac.com to express interest and find out more.

Read on for a little on Andy’s journey of oyster discovery, below…

Just before a global pandemic was declared on 11 March 2019 and shortly before lockdown V1.0, I read a news feed item from BSAC entitled BSAC supports Zoological Society London’s native oyster quest.

It informed me that there has been a 95% decline in the population of the native Oyster Ostrea edilus over the past 200 years due to a variety of effects: historic overfishing (in the 1800s in particular), habitat loss, pollution and the introduction of diseases.

The briefing went on to get my interest because, as a professional engineer interested in seabed restoration, it started with a problem definition – essentially the seabed doesn’t need conserving but rather needs restoring. As an engineer, my job is about solving problems. The press release went on to say:

Alison Debney, ZSL’s Senior Conservation Programme Manager said:

Throughout our restoration work – one of the barriers we’ve come up against is not having images of native oysters in the wild. Trying to explain the importance of a species to people when they’re only ever framed as a seafood dish can be a struggle.

Oysters provide enormous benefits in the form of ecosystem services; nurseries for wildlife, clean water and in abundance, removal of carbon from our environment into their shell to name a few. Whether you’re a diver, photographer, fisher or simply live near a coast – we need your help. The native oyster is a forgotten British treasure that needs the public’s support during this long road to recovery.

Now that I live down South next to the Solent, I couldn’t help but be attracted to the fact that being filter feeders, they also clean the water. What would the water quality be like if oysters were back to full strength? I couldn’t help but wonder that if an adult-sized oyster can filter up to 200lt of water per day, how many would be required to turn the Solent gin-clear; I concluded an awful lot more than what is currently on the seabed!

I read about the competition and prize so I was now on a mission to find and photograph oysters in conditions that are rarely gin-clear (although as it transpired 2020 was a better year than most down in the Solent).

Now, I’d noticed occasional ones around on dives around the island before but never paid them much attention as there was probably some rust, a lure or some other nice, easier to find marine life to look at.

Oysters can form amazingly large reef structures but there are no known examples of these reefs left in the UK. They disappeared long ago and we certainly didn’t make any fantastic scientific discoveries to the contrary. They are also usually quite hard to spot blending much better with their surroundings than say a scallop which is also a rare find on dives around the Isle of Wight.

Once lockdown eased and shore diving was back on, the hunt for oysters became a theme or aim of each of the dives and as we spotted more of them, my eyes and those of my buddies became tuned in to what we were looking for.

Initially, we started finding them under local piers in amongst eelgrass in particular, but also clinging on to pier legs and other hard substrates.

We did find what could just about be classified as an oyster bed (>5 oysters per square metre) but most of the time, we found them in small clumps and reasonable widely spaced, and quite often covered in sponge making them even harder to find.

We looked up from the seabed and started to spot them on vertical walls, on and inside wrecks, sometimes hanging upside down away from their usual predators (starfish, crabs, seabirds and humans!)

Before long, contact was made with a fellow BSAC diver and professor at Southampton University, who in turn put me in contact with Dr Luke Helmer, a researcher on the Solent Oyster Restoration Project (SORP) run by the Blue Marine Foundation. He then proceeded to bury me under a huge amount of scientific literature for me to read. So here is a summary of what I’ve learnt above native oysters so far:

- In 1864 – 700 million oysters were consumed in London alone and were essentially the food of the poor.

- By 1886 – Only 40 million landed by fisherman down from an estimated 500,000,000 per annum. Oysters were becoming the food of the rich.

- Native oysters were widely distributed around the UK but less common in the east and northeast.

- Oyster reefs typically form from intertidal mudflats (0m to 80m and so should be able to be spotted by all levels of diver and snorkeller alike).

- They like some tidal flow (1-2knots) and temperatures above 8-9°C.

- They can bio-accumulate contaminants and algal toxins that cause illness in humans.

- They can filter up to 200l of seawater per day.

- They absorb nutrients such as nitrates and nitrites that cause algae blooms and this help absorb nitrates flushed from the land.

- They have the potential to absorb carbon dioxide from the atmosphere and lock it away in their shells.

- Oyster reefs can provide increased fish production by providing a nursery for juvenile fish.

- They are on the list of threatened and/or declining species and habitats.

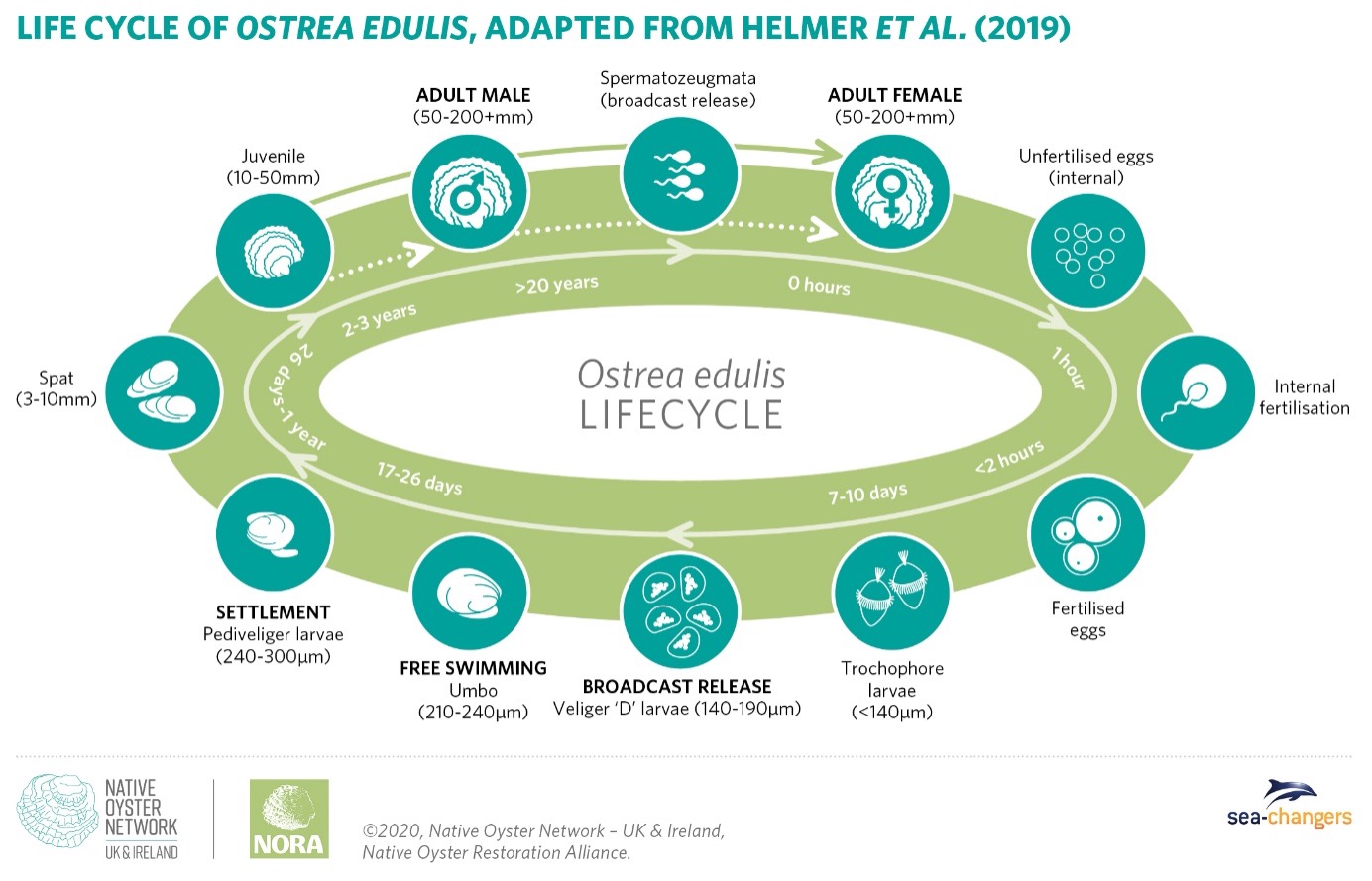

- They are protandrous hermaphrodites (i.e. they can change sex) alternating genders with each breeding attempt (typically between May and June when the water temperature rises).

Lifecycle of Ostrea edulis (native oyster) courtesy of Dr Luke Helmer et al. 2019

Full reference: Helmer, L., Farrell, P., Hendy, I., Harding, S., Robertson, M., & Preston, J. (2019). Active management is required to turn the tide for depleted Ostrea edulis stocks from the effects of overfishing, disease and invasive species. PeerJ, 7, e6431.

Preston J., Gamble, C., Debney, A., Helmer, L., Hancock, B. and zu Ermgassen, P.S.E. (eds) (2020). European Native Oyster Habitat Restoration Handbook. The Zoological Society of London, UK., London, UK.

Most normal branch reef and wreck dives took on an added element of a science project. Indeed, shipwrecks could be suitable to use as locations for helping restore the population of oysters in the future but more scientific research is needed to back this up.

With my BSAC Expeditions Officer hat, I’d like us to build on the success of the BSAC contribution to the Scapa 100 project which involved multiple branches from all over the UK with some bespoke BSAC Expedition Scheme trips that catered for direct members and indeed members from overseas.

BSAC is therefore launching Operation Oyster to help continue the research for Oestrea edulis particularly with regard to their location on shipwrecks and reefs but also on shore dives and indeed walks on the beach to gather useful data for the scientific community as an input for their work to determine how best to restore native oyster populations.

Now, I had to look at the annuls of club history back to 1967 (before I was born!) for an example of a similar undertaking by the organisation and that was Operation Kelp organised by the late Dr David Bellamy back in 1967 who used kelp to monitor pollution levels in the North Sea. So, I finish the article with a call for expressions of interest in participation in Operation Oyster from individuals and clubs.

Want to get involved?

Andy needs a core team of about four volunteers with skills in marine science, video editing, social media and applying for grants to help me run a large BSAC citizen science project. He also, in time, will need members, clubs and centres to participate to help deliver the project.

Contact Andy at expeditions@bsac.com to express interest and find out more.