Why protect seagrass?

Seagrasses are the only flowering plants which have adapted to live in the ocean. There are at least 60 species of seagrasses around the world. Along the UK coastline there are two ‘Zostera’ species of seagrass, Zostera marina and Zostera noltii which live in shallow sheltered waters. Like plants on land, seagrasses use light to photosynthesise, grow with their roots anchored in soft sediment and reproduce by producing seeds. Seagrasses grow long, thin, green blades to capture the sunlight and can look just like underwater meadows.

Benefits of seagrass

Seagrasses have been described as one of the most valuable coastal and marine ecosystems on the planet. They lock away carbon, provide an important habitat, protect our coasts and are an amazing place to spend time.

Carbon storage

Some research indicates that seagrasses are responsible for 15% of the ocean’s total carbon absorption, and that globally they are 35 times more effective at locking up carbon than rainforests. This process of organisms locking up carbon in the ocean is often referred to as ‘Blue Carbon’. Natural processes like this which benefit humans are called ‘Ecosystem services’. Ecosystem services like this blue carbon storage are likely to play a vital part in the future management of climate change.

Important habitat

Seagrass beds provide shelter for a wide range of marine life to flourish, including juvenile commercial fish species and the elusive seahorse.

Coastal protection

By binding loose sediment together with their roots, seagrass beds protect the coastline from erosion. This is likely to become increasingly important as extreme weather events happen more frequently as a result of climate change.

Threats to seagrass

Despite all of the wonderful things that seagrass does for us and the environment, its habitats are under threat from a variety of factors. It is estimated that beds have declined by an estimated 92% from their historic extent. Around the world an area the size of a football pitch of seagrass is lost every 30 minutes. This is due to decreasing water quality, physical disturbance of the seabed, coastal development, disease and increasing siltation.

Once seagrass beds are lost the species that live in them will also be lost, along with the stabilising effect that seagrass has on the sediment. The seabed becomes loose, moving around like sand blown across a desert. Once this has happened It is very difficult for seagrass to re-establish itself in this unstable environment.

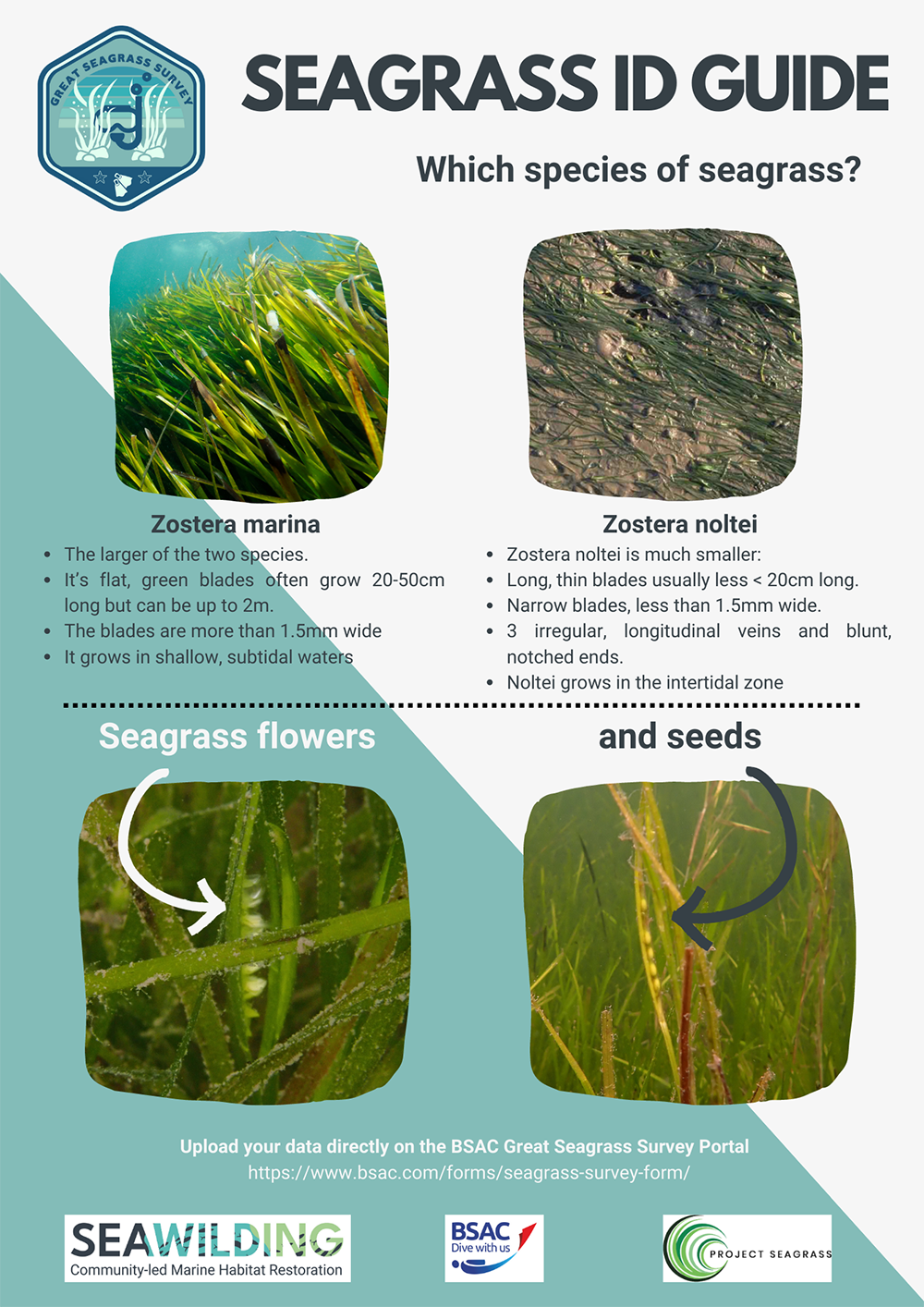

Identifying seagrass

There are two main types of seagrass which you are likely to find in waters around the UK, Zostera marina and Zostera noltii. Here's how to identify each one:

Zostera marina

- Zostera marina is the larger of the two species

- It has the widest range of any flowering plant in the northern hemisphere

- Its flat, green blades grow to between 20 and 50cm long

- The blades are more than 1.5mm wide

- It grows in shallow, subtidal waters - meaning that it is underwater at all states of the tide

Zostera noltii

- The blades are also long and thin, growing to a maximum of 22cm long

- The blades of Zostera noltii are narrower, less than 1.5mm wide

- They have three irregular, longitudinal veins and blunt, notched ends

- Zostera Noltii grows in the intertidal area - meaning that you may see the blades lying on the beach like clumps of fine green hairs at low tide